Blog

Johannesburg: race, history and other controversial topics

Johannesburg: race, history and other controversial topics

January 11, 2018

It’s almost compulsory to share my perspective on the racial and cultural divides in Johannesburg having spent my first 6 days in South Africa here. My obligatory disclaimer is that this is one person’s perspective seen through the lens of a liberal feminist New Yorker and child of an immigrant. There – I laid my biases out on the table. Now onto the perspective…

I’ll preface by stating that the most common response I received when telling friends and family I was starting my world tour in Johannesburg was “be careful”. My initial reaction? Psst. I’m a New Yorker, people. It can’t be much worse than the South Bronx and I feel relatively secure roaming around there (at the right time of day, of course). All major cities in the world have varying levels of crime, typically concentrated in specific areas. Generally speaking, the nature of the crimes, most common offenders and neighborhoods where rates are higher are products of the region’s history. My view is that, sadly, when there are concentrations of people of color and poverty, the neighborhoods by default are labeled unsafe. Turns out, Johannesburg is no different.

Johannesburg, the largest city in South Africa, is also known to locals as Joburg, Jozi, the City of Gold and, at one point, “Little New York”. The very brief (dumbed down) history on this remarkable city is as follows. The city was established in 1886 when gold was discovered in the farmlands, later making it the largest gold producer in the world. The Dutch had already arrived in South Africa a few hundred years prior followed by the British in the early 1800s. Laborers were brought in from countries all over the world to do the dirty work with little gains.

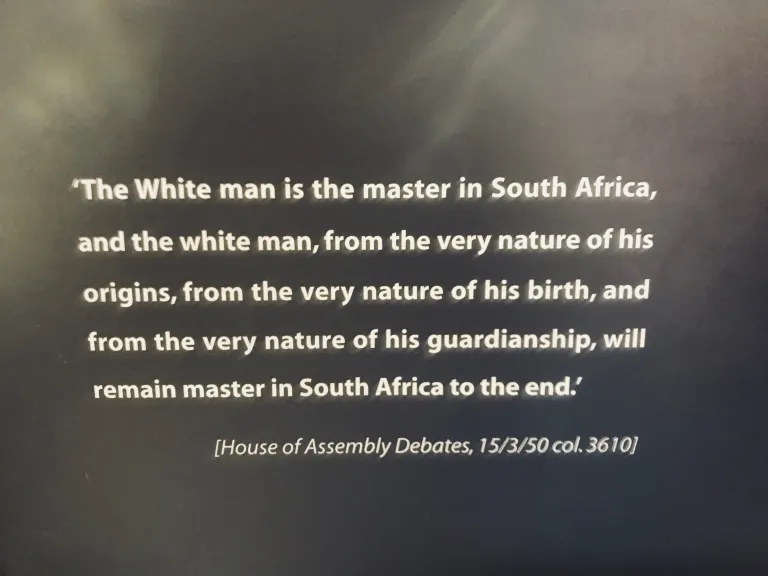

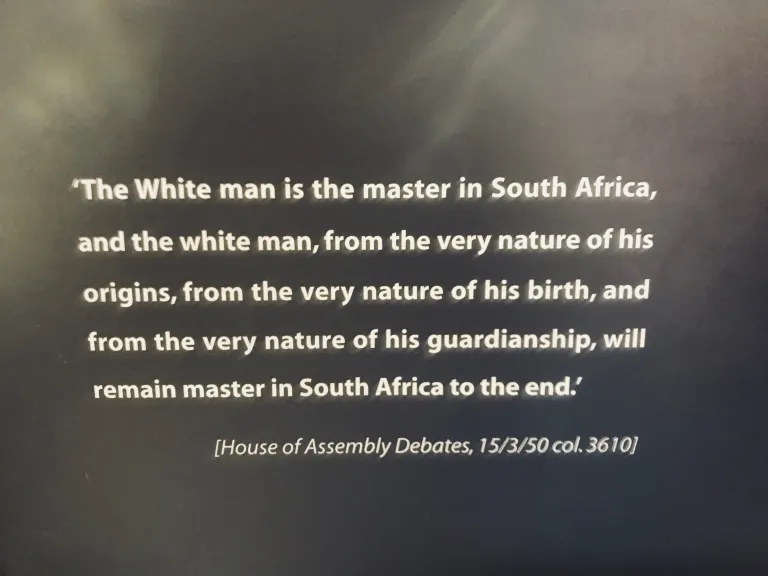

The European “settlers” (I dislike this word and prefer the term thieves) had the primary goal of making this city a “whites only settlement” so they planned the infrastructure accordingly, pushing the native African population out of the city into an area of settlements known as Soweto, or “South Western Townships” around 1948, when Apartheid was born and became law. The townships were basically equivalent to projects. This was one of many examples of intentional systemic oppression to ensure Africans and other non-whites could not move up the ranks, along with an unevenly designed education system and limited low level job opportunities. Sound familiar?

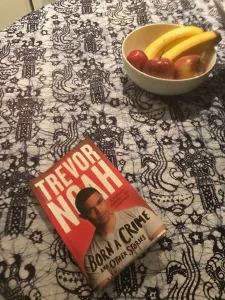

People were placed into racial groups based on skin color. There were two major groups: non-whites and whites. The non-whites consisted of Africans, Coloureds (mixed race) and Indians. Whites consisted of the original Dutch settlers (there’s the unsettling term again), known as Afrikaners and other whites. Apartheid ended in 1990 (just 27 years ago) when Nelson Mandela, a revolutionary anti-apartheid leader, during negotiations of his release from a 27-year prison term insisted it was part of the deal. That’s right – he spent 27 years as a political prisoner fighting for freedom and equality, was offered release and insisted that continuation of Apartheid was a deal breaker. One of the most remarkable outcomes of this was that Mandela became president shortly after he was release and the country’s oppressors were forgiven. The approach in South Africa was in stark contrast to the methods of justice against other countries with historical human rights abuses and atrocities. Post-Apartheid, with the primary goal of avoiding further violence, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was formed in 1994 along with three other subcommittees. Its responsibility was identifying victims, by a set of definitions, granting reparations, granting amnesty to the accused where warranted and often to just record and validate victims of abuse. Ultimately, there were no consequences for the murderers, torturers, slave-owners, rapists, and other vile criminals who created this inhumane system. One view is that this was a necessary and forward thinking approach to ensure a peaceful transition. Another is that it contributed to a seemingly complacent society surviving a brutal history of exploitation and oppression. Both are likely correct. Here’s a great NYT piece from 2015 on the ongoing controversy of land apartheid: In South Africa, Land Apartheid Lives On. Additionally, Trevor Noah, in his book Born a Crime, offers a deeply personal and incredibly insightful perspective having been born and raised during Apartheid in Joburg. If you’re a fan of Noah, I highly recommend it as his persona shines through from beginning to end.

I spent 6 days exploring Joburg and visited a variety of neighborhoods – Soweto, Hillbrow, Sandton, Bedfordview and Gauteng. I didn’t feel unsafe in any of them – likely the New Yorker in me. I spoke to several locals, many of whom were born during the era of Apartheid. I shared that I had a very visceral reaction to what I saw as the obvious products of Apartheid. The whites maintain wealth and status, own the majority of the land and businesses and live in the expensive neighborhoods. “It will take time”, was the response from my African Uber driver who happened to be a friend of my cousin. His view was that as Africans get a proper education and become successful, things will change. Most other locals I spoke to said they never really experienced overt racism. Little comments were brushed off. Perhaps that’s a behavioral side effect of the decision to forgive and forget. According to my tour guide at Constitution Hill, like in America, South Africans are not taught the details of the brutality of Apartheid in school. Many white South Africans view it as an uncomfortable ugly little secret of the past that we don’t really want to talk about. He shared that one museum visitor even rationalized it saying, “that’s just what you did back then”. This defense mechanism is not unique to South Africans.

I, myself, experienced overt racism for the first time in my life. Having been brought up in an all white community in New York and being a first generation Indian American, I experienced plenty of prejudice and teasing growing up for simply not being white. But it stemmed from a place of ignorance, not hate, or so I’d like to believe. This was a very different feeling. I’d like to reinforce that despite this incident, my experiences with the people in this country, white, African, Indian, etc. have been noting short of lovely. But this experience is worth sharing particularly because we are living in a time where the core democratic values on which my own country, the United States, was established are being tested. While on our journey to Kruger National Park, my cousin, his wife and I stopped at a grocery store. A woman was staring at me while in line for the cashier with what I perceived to be a look of disgust. Being the optimistic person that I am, I thought surely I was mistaken so I smiled at her. She shook her head and showed more disgust. I turned away not wanting to assume but pretty confident I knew her issue. As my cousin’s wife and I walked out of the store together, the woman walked up behind us and pushed us out-of-the-way saying, “get out of my way”. I asked if she was a racist and, without turning, she gave us a thumbs up. She turned around after and said, “you need to go back to India”, and quickly rushed to her car. I was initially paralyzed with disbelief then quickly filled with rage and sadness at the same time. I looked around for witnesses, a security guard or police officer, but there was no one close enough who heard. My cousin encouraged me to let it go. Let it go. Turn the other cheek. That seems to be the most common reaction you will hear. The interaction with that woman evoked within me a much thought and emotion. I realized there are obvious parallels between South Africa and the US both historically and at present. The wounds are just fresher here but the scars don’t disappear. Within 24 hours, I negotiated through those feelings and decided to let it go. Despite this incident, what was encouraging to learn from the locals is that racism in South Africa is strictly punishable by law to a degree we can only aspire to in America.

In a time when we are all being tested to confront our fears, biases and true intentions behind our everyday behaviors towards groups who are dissimilar to us, I encourage you to employ a deeper level of independent thought. From birth, we have all been taught to believe certain stereotypes about religions, race, gender and socioeconomic status. If we are just adopting the views of others without looking for understanding, then we are not independent thinkers. We are just followers.

Visiting Joburg taught me that if I had listened to the fears and biases of others, I would have deprived myself of a worthwhile experience that, along with future experiences on this journey, will shape me into a better future self.

Discover more from diannajacob.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Recent News

About Dianna

May 29, 2024

On Being Single and Child-Free

July 31, 2022

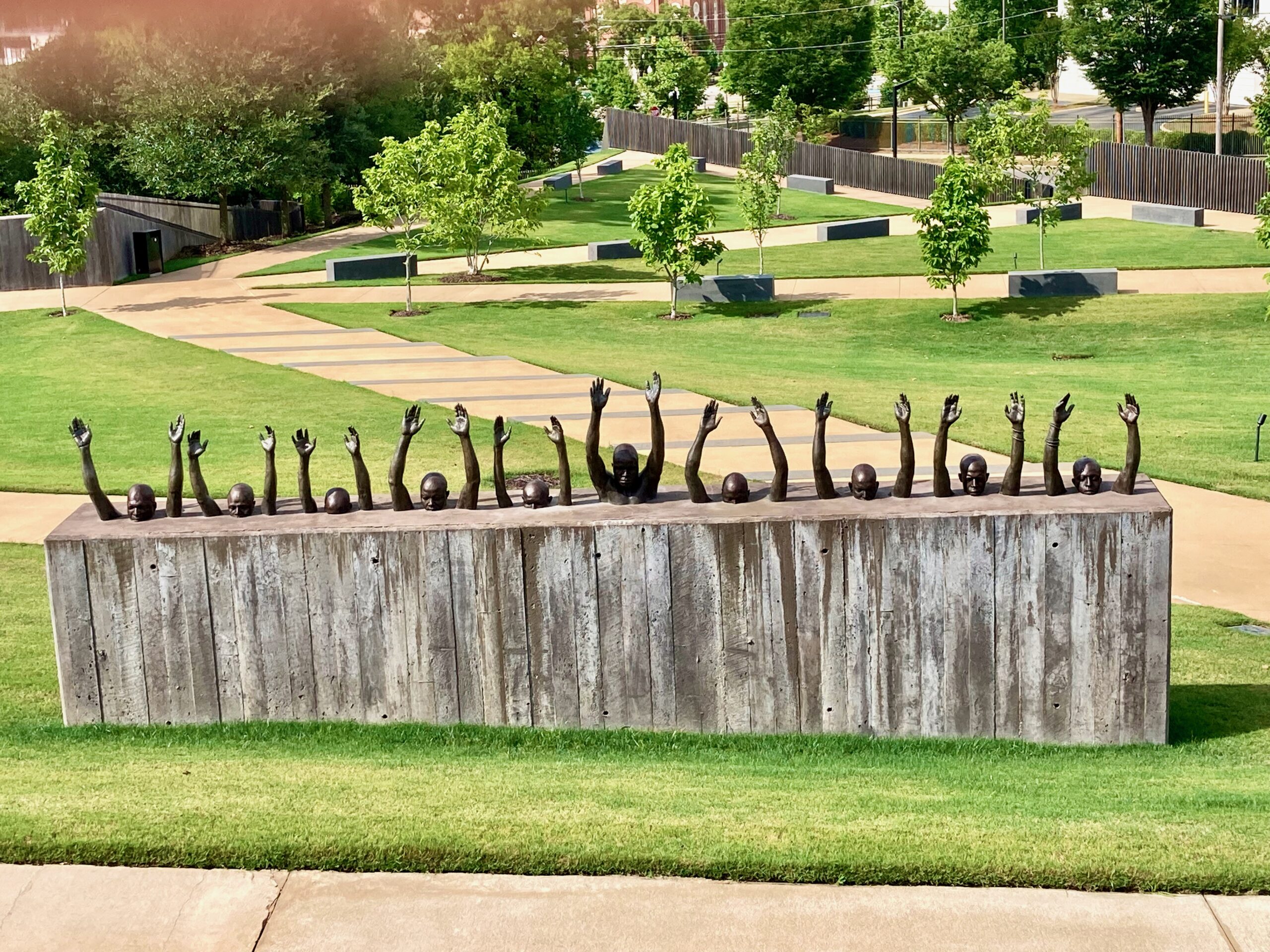

Relearning American History: A Self-Guided Tour of the South

July 7, 2021

Racism: A Global Pandemic

June 8, 2020

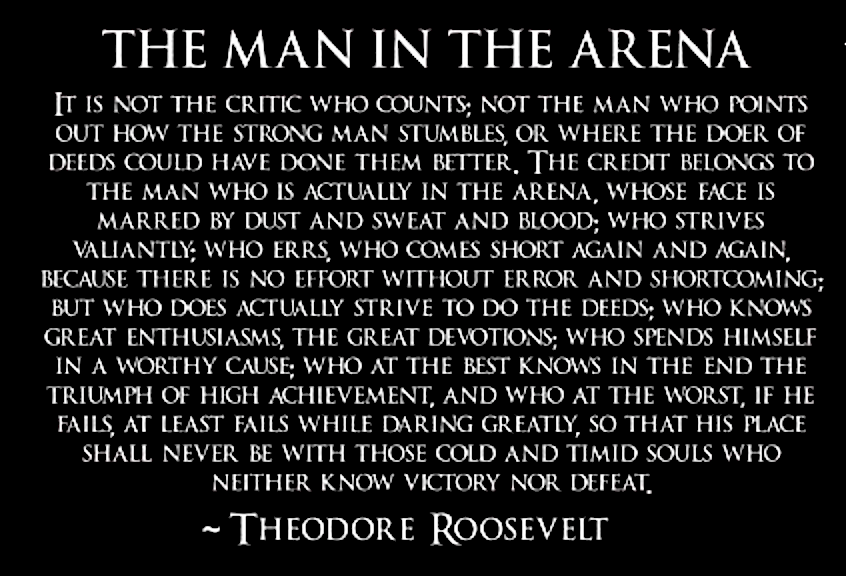

Daring Greatly

August 23, 2019

Becoming a Better Me

January 10, 2019