Blog

Tanzanian Healthcare, Part III: The twisted economics of patient care

Tanzanian Healthcare, Part III: The twisted economics of patient care

February 26, 2018

In my earlier post, I shared challenges associated with effective clinical care delivery at Dareda. This last post in the series, I explore the economics of patient care. Before you continue, it’s worth a quick skim through the background on Tanzanian healthcare here.

In exchange for their generosity in hosting me, I offered free management consulting to the hospital leadership. They were quite enthusiastic about the idea as they hold US healthcare providers in very high regard. They were also very transparent about the hospital’s strengths and weaknesses. This was key to conduct an honest assessment. I provided what’s called a SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) along with a set of recommendations. The ten-thousand foot view is that the hospital is extremely financially unstable. It needs an aggressive plan for the next year to decide whether a turnaround is possible.

Dareda is a private hospital with a renewable three-year contractual partnership with the government dating back to 1998. This partnership provides Designated District Hospital (DDH) status, allowing for subsidies in the form of direct salary payment for about half of the staff, funding for certain medications and medical equipment. With this designation also comes adherence with government policies, the most impactful of which is free healthcare for maternity and pediatric patients under five. My first reaction to this was positive – women and children get free care. Then I looked at the hospital statistics. Roughly sixty-eight percent of patients discharged from Dareda Hospital are maternity and pediatrics under 5 years. That means sixty-eight percent of their cases do not generate revenue. Some of these patients do have insurance but, due to lack of education, fear and mistrust, many will not share their insurance information with the hospital. In order for this partnership to be of value in the long-term, the combined revenue from the government and the other thirty-two percent of patients must exceed the total expenses for the hospital. This is not the case at Dareda.

The other key statistic was that sixty-two percent of patients are self-pay, which means they lack insurance and pay out-of-pocket. They also represent the poorest populations from the villages. By in large, they do pay their hospital bills but at what price I wonder. Even health insurance, if you’re lucky to have it, has caps on number of household members covered. Most Tanzanian families exceed those caps. The cost of medical care presents a great burden on the citizens no matter what their insurance status.

The hospital has no cash reserve. The hospital’s revenue equals its expense. Unlike individuals, businesses generally avoid bank loans out of fear of being unable to repay them. They are completely dependent on the revenue from the thirty-two percent of patients who are self-pay or have insurance, the timing of which is unpredictable.

In my short two months traveling, I’ve learned we are more similar to our global neighbors than we are different. Government makes promises but doesn’t deliver. Of the total expense budget the hospital developed, the government paid less than 50% citing funding was unavailable. Health insurance companies practice an unfair payment system. They reimburse district hospitals up to 30% less for the same services than at hospitals with a higher level of care.

People with means have an advantage. They will get high quality patient care. They have options to go to private hospitals that have to more resources and the best specialists in the regions. People without means are left with either a government hospital, which is known to offer a lower quality of care, or a facility like Dareda, which strives to deliver excellent care yet is highly under-resourced.

So, I sit in a very conflicted place, developing a set of recommendations to improve the operations of the hospital. I believe healthcare is a right, not a privilege. I’m a strong proponent of universal health care. At the same time, I struggle to develop realistic short-term recommendations for survival that do not entail worsening the burden on the poorer self-pay patients. In the long-term, taking on the insurance companies, investing in specialty services and challenging the value of the government contract renewal will be critical for success.

My time here has been an unforgettable experience rich with learning and new friendships. I have great confidence that this management team will make the best decisions to advocate for their patients and the community. Over the next few years, I hope to hear that the hospital is thriving and that they are no longer heavily reliant on their daily prayers being answered.

Discover more from diannajacob.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Recent News

About Dianna

May 29, 2024

On Being Single and Child-Free

July 31, 2022

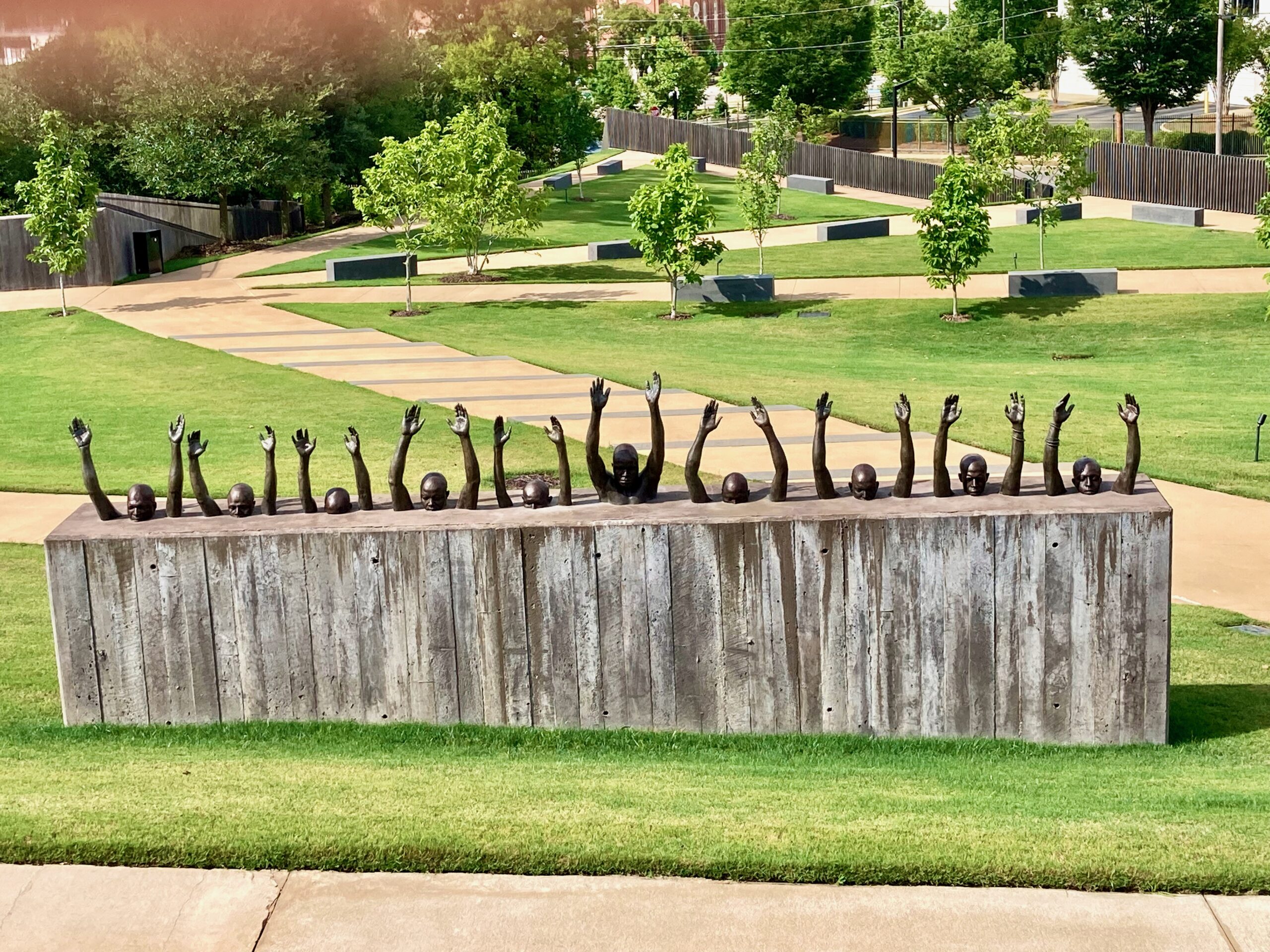

Relearning American History: A Self-Guided Tour of the South

July 7, 2021

Racism: A Global Pandemic

June 8, 2020

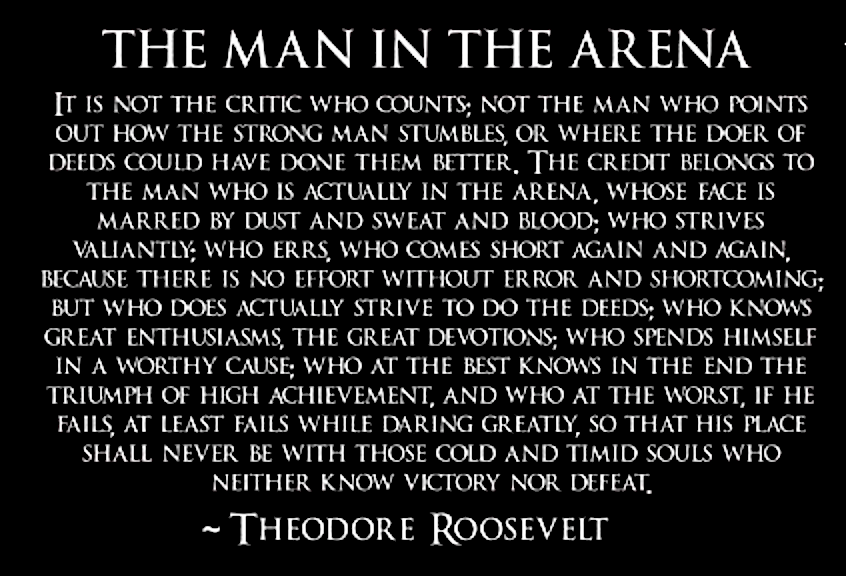

Daring Greatly

August 23, 2019

Becoming a Better Me

January 10, 2019